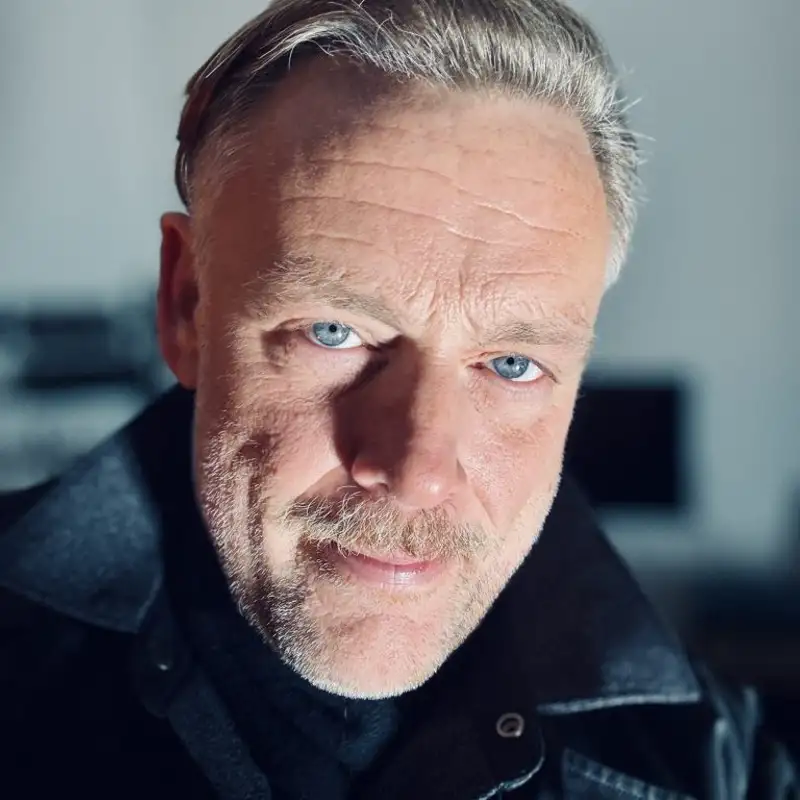

20: Andrew Melchior

This is an automated AI transcript. Please forgive the mistakes!

This is the Iliac Suite, a podcast on AI -driven music. Join me as we dive into

the ever -evolving world of AI and music, where algorithms become the composers and

machines, become the virtuosos. Yes, this music and text was written by a computer,

and I am not real, but… I am and my name is Dennis Kastrup.

Hello humans, welcome to a new episode of the Iliac Suite. I'm honest with you

today. The last four weeks were actually pretty quiet in the field of music and AI.

No ground -breaking news, I have the feeling. Is it because all has been done?

Is it because the world politics are taking all the attention? Is it because it is

winter in the Northern Hemisphere, or is it because I'm not up to date anymore.

Maybe it is a mixture of all these points, except the last one, of course. But in

the end, there is always something to talk about. And this time I invited someone

who is working in the field of music and technology since ages. His name is Andrew

Melchior, or in English we would say Andrew Melchior. A friend of mine suggested me

Andrew for an episode because he said that he has so many interesting things to

talk about. So I reached out to Andrew and I'm very happy that he said yes.

But before you will hear our interview, I would like to give you some more

information about him. I asked this lovely AI voice to tell me more.

Melchior began as a classically trained pianist and later explored digital music

production and internet technologies, leading to a job at EMI Music. His career

expanded into photography, digital energy, and augmented reality, eventually working

with Magic Leap and renowned artists like Björk and Massive Attack. He played a key

role in innovative projects such as Björk Digital, the VR album Vulnicora, and AI

-driven music experiences. Since Covid, he has been a freelance artist working on AI

-driven creative projects, including a Sonic artwork for the European Capital of

Culture, 2026 and an AI -powered spatial audio experience in Poland.

Pretty fascinating I think. I'm honest with you, before the interview I had

originally planned to talk with him about artificial intelligence and music and the

ecological impact of that, because since months I also wanted to produce an episode

about that problem that we use so much energy to generate music but I postpone this

now to another episode in the future. We had some words Andrew and I and we talked

and we just got a little bit lost in the flow and we had so many different

subjects to talk about so I just let it go and I can say it was really really

worth it. I leave you now with the interview where Andrew first of all tells us

what he is doing at the moment. - Currently, I'm working out of my home studio in

Krakow, where I'm based currently in Poland, and I'm developing a couple of projects.

One of which is a European Capital of Culture commission. I have for 2026 in Oulu

in Finland, and that is basically a sonic artwork I'm designing with a guy from MIT

called Professor Kiyoshi Masui, and it's using sonifications of fast radio bursts,

which are these cosmic intergalactic radio signals, which are some of which are very

old, coming from the other side of the galaxy. And basically I've worked as a Masui

to sonify 500 of about 4 ,000 that we've recorded since 2001 and those are being

installed into a cathedral in Olu which is just outside of Lapland in Northern

Finland as part of their Capital of Culture celebrations next year and it will be

an installation with the hardware company Genelec. We're building this 12 .4 speaker

system inside the cathedral and we're basically pulsing these sunifications into the

space using a bunch of code, time of day, time of year and crossing over between

both the astronomical data as well as the religious data to try and create a

conversation between science and spirituality so I'm doing that at the moment and

then another thing I'm working on which is more AI but not musical AI actually

interesting it's to do with spoken word whilst living in Krakow I'm working with the

Jewish Cultural Festival here there Krakow was one of the ghettos that was liquidated

by the Nazis at the end of the Second World War and so there are a lot of

buildings but no people related to the buildings, so I've been working with them

here to build a location -based audio narrative which will allow the visitors who

come to the Jewish Cultural Festival the opportunity to listen to voices of previous

inhabitants of the city talking about their experiences in the Jewish Quarter and

things like that, and we'll be using an interesting overview for that we're using 11

labs and a bunch of location -based audio triggers based on geofencing to generate

procedural narratives in different languages. And the first project was not involving

AI, you said, right? No, that's right. I mean, to be honest,

we can go into this detail now because obviously that's the reason you're using this

conversation, but everything in anything code -based,

you can find excuses to use AI at the moment, but I didn't feel that that was

necessary for this, so I've been using Super Collider, a software tool, to build a

programmatic, sort of, planetarium in a way, which will

triggering these audio samples that we've created to these sonified radio bursts. And

there wasn't really any reason to use AI. We weren't trying to clean up any weak

signals not a space because these signals are not within human hearing range. So

this was more about scripting data into sonic form to create representation of the

radio bursts. So with that, I didn't need-- - Yeah, I didn't need-- I mean, what I

found out also in the last years, I mean, people using AI, when I started to cover

AI in music, actually, in the beginning, I had the feeling people were using the

word AI just so I cover them. They were like, if I use the word AI, the

journalists will come and talk about this. And it was like this in the beginning,

but people were using it just to get attention after I had the feeling. And

sometimes I was not even sure if it was AI because you could never prove it in

the end. I mean, somebody can tell me that's what I've done with AI, but in the

end, it was not done with AI. Have you experienced this also in the late, I don't

know, years or, yeah?

- Yeah, so interestingly, if we go back in time with it, so about 10 years ago,

I Did some work for a company called Magic Leap and Magic Leap were building

augmented reality glasses They were Google funded and they were building real -time

mixed reality hardware that you would wear on your eyes and the idea was to create

music and video and graphic and game experiences for that.

And during that process, I got to work with Massive Attack and Sigurros and Björk

and a bunch of other artists, which was good. But what was interesting at the time

was we were looking at how wearables like that could change the experience of

listening to music. So we did a Robert Del Nia and myself, the founder of Massive

Attack, we met and started discussing sort of concepts for a music player that would

basically try and understand how music could be created and consumed on a device

like that where you had location data, you had time of flight,

time of day, you would even have eye tracking, maybe gestures, and obviously binaural

spatial sound with head tracking. So we bundled all these ideas into an app that we

built originally for iPhone called Phantom. And it was like an art project.

It really wasn't really a commercial project. And interestingly, Johnny Ives, Robert

knows Johnny. I'm like, Robert knows everyone. And Robert knows Johnny Ivan. We ended

up going to Cupertino and Johnny went, Oh, here's, here's a new thing called the

watch. - And so we got very early access to Apple Watch and what we were able to

do with that was use the heart rate as well as all the other data from the phone,

including the camera and the screen. And originally, I did understand how we could

have tried to use AI for that, but at the time, the models weren't there.

I mean, we didn't, it was too early. We were kind of, we had a good idea, but it

was too early to execute in the way you would do it now, for instance. So based

on your question, yes, humorously, we used to call it mandraulic.

So instead of AI, people go, oh, how's the software kernel working? Is it AI? We'd

go, no, it's basically it's forced pattern language program by sensors,

sensor fusion. And we would have to go into the way the application worked,

as we would feed its stems from songs. And then we would write a set of rules for

this bass line with those drums, but never with those vocals, kind of, you know,

and /or operators for these stems to keep some of the musicality of the remixes.

But it wasn't AI. And interestingly, even with the developments in AI now,

it would still be interesting to see what it spit out because I'm not convinced

that the composition is still, you know, something that is, if you're going to do

very mechanical, repetitive techno and things like that, I suppose you wouldn't notice

as much. But with songs, interestingly, with songs with a human touch,

I still feel it's quite easy to recognize this sort of canned version of sort of

creative music, Maki.

- I was just like, I just had a quick idea. You were not part of the Björk

installation on a hotel where they were using choirs? - No,

that was Arka. No, I had a chat about that, but that was Arka. And so Arka and

I, we had a chat about this years ago and he ended up doing this thing with the

IBM, yeah, in New York with it with a lobby. And that was interesting.

Again, that was I think with bronze. So there was this platform called Bronze that

spun out of Goldsmiths College in London, who Robert and I actually also work with.

And they were building this platform that is going to sort of real -time create

music. just to explain to the listeners. I did a report about it. It was in a

hotel in an installation and on the top, I think they were watching the sky or

taking data from the sky and using pre -recorded choirs of Björk and her choir or

some choirs. And they were changing the music in the sense how the weather was

changing. but yeah, it was on top of the... - That's right, it was called Kursafan

originally. I see, just remember, it was with Microsoft. - Yeah, yeah, yeah, I

remember this.

- And interestingly, well, I'll tell you a secret story, which is now not going to

be secret, but the thing they were doing with that was she had her choir in New

York ready for the Kornikopia tour, which was launching at the shed. and they had

this very large choir and to give them all something to keep them occupied also

waiting for the sets to be built and the orchestras to come together they basically

did this fun little side project as I say it was it was I think it's AI -generated

music but it was Juliana Barwick I think composed it I don't remember the name and

there was a score that Arca wrote using bronze AI engine Well, if we are here now

telling stories to people who have never heard these stories, I can tell you a

quick story about Björk too, because I was at a festival in Finland at the Flow

Festival, and I remember I was going out late, and I had some fun, I had some

drinks, and one of my friends said, "Oh, we're going home now." Björk was playing

there the night before, the evening, and they was like, "Oh, we're going home now."

I stayed in the same hotel as the artist, I remember, and I stayed 10 more minutes

late for another drink, and then I went home in the hotel. I slept, I woke up in

the morning.

She invited everybody to go into the suite and we were like singing all night long

in the suite with Björk and dancing and at one point I was sitting on a bed and

I was talking to a girl and she said, "Oh, my name is Feist." And I was like,

"And I just missed this by 10 minutes because I was having another drink." So

that's my story. But it was a wonderful night, I've heard. We were here a podcast

about AI and music, music, talking about AI music, maybe you can, as you're in that

field, you're, you're working with this and you're, you're experimenting, uh, a lot

of new inventions and new roads there. Maybe tell me a little bit about how, how

you embraced or maybe later on not embraced AI in the sense that it came into your

life and you were interested and it thought, Oh, those possibilities are on the

horizon. This this will happen, and this is what excites me about it. Maybe tell me

a little bit the story of you and AI. So, I was first really interested in AI for

writing music by a project that was started by Google called Magenta.

And Google Magenta was set up by a guy called Doug Eck. And Doug Eck and a bunch

of his team were basically working on developing sort of these generated scores and

his studio. The idea was to build a sort of studio

interpolated tool that would allow you eventually ended up being integrated into

Ableton, things like that and it And they were basically training models using open

source performances and materials. And they were,

to a greater or lesser degree, had some interesting experience with drums and sort

of generative content rather than necessarily using style transfer.

And they ended up building this midi plug -in which sort of had a groove and a

generated and drama -phonic kind of interpolated function.

And yeah, and that was the first time I really got interested in that. We, we,

Robert Del Nage and I were definitely interested in that area because we were

working with this company making augmented reality headsets. We were interested in

this sort of generated soundtrack ideas.

So the phantom player that we set up would, the way we built it was it would use

data points from your device and it would generate mixes based around the integers

coming into your device from the camera and the clock and the heart rate and

things. So we were very interested in where this was going to lead with AI and so

yeah I I was in on the Duggeck experiment for a while. It was about that time.

I also came across a guy called Sander Diehlmann. And Sander Diehlmann was working

for a deep, about a deep point. It's a deep mind. And they set up a thing called

Wave Nets. And Wave Nets were quite controversial at the time because Google decided

not to release them because they were incredibly good at mimicking the human voice

very quickly, just from like a minute's worth of audio. And interestingly, that

product now seems to be what is 11 Labs, five or six years later.

But originally, they decided not to release anything like it, because I don't think

so. But it's interesting. I'd be very interested to know where the source code for

11 Labs comes from, because there's not much talk about that. But yeah, we

originally worked with Doug Eck and that team. And then I was then also aware of

working at Goldsmiths. So we, Goldsmiths University in London,

the University of the Arts was doing quite a lot of work also with AI.

And I introduced the work that I was doing massive tack to a couple of their

academic team. And that ended up being a project that sort of morphed into an

exhibition at the Barbican that we did, which was called More Than Human, which is

part of a Google Arts and Culture project.

And I think we also ended up doing a thing for UK research and innovation. It was

a project called MIMIC, And we did that with Mick Griss,

and it was a course leader at Goldsmiths at the time. And it was using sort of

wave nets, magenta, it was messing around with sort of convolutional neural networks,

recurrent neural networks, all the sort of buzzwords at the time. And we were trying

to sort of humanize some of the output of that really. And so yeah,

so this is the kind of where my entry point was and that was at the time quite

academic It wasn't commercially available software. It was quite a lot that was blue

sky sort of

Bootstrapped Software that had to run in a custom wrapper and you had to know you

were doing with the models to do the training Not kind of stuff and that's kind of

where I was, I was introduced to the idea. Now, just to go into that slightly

more, I was Caspi trained pianist, so I know about things like player pianos,

and I was always aware of Midi from a long time ago, because I was born in the

70s, so by the 80s when Midi first turned up, I was one of the first kids on the

block to have a midi keyboard, I got a Krumar Bit 99 along with a guy called

Graham Massey who was in 828 State in Manchester and there was this crazy music

shop called Chase run by a couple of Sikh brothers and they had these amazing and

for some reason they had this amazing set of keyboards that were in the Italian

company Krumar and you could buy these crazy midi for the first version sort of

quite clunky midi keyboards so I've been experimenting

- Five, I think 86, quite really early, right? So Dave Smith had obviously decided

the MIDI thing and Cruma were the one of the first to create this sort of,

this thing called the Bit19, well, the first was Bit1 and then the Bit99. And so I

started connecting roll and drum machines to MIDI keyboards very early on and doing

weird stuff. And so I've always been aware of things 'cause I was also very early

doing days with Cubase and Cubase on the Amiga, running on Simpty Stripes on 16

-track tape decks. And then the good old days.

And then I was also aware of, obviously, as VST came in, I started direct to this

recording. So I've always been aware of the tech.

And... Yeah. That's interesting. If I hear this now, it's really interesting. I just

have one question for you quickly for that. It's like, because you're always

interested in the tech stuff. Was the interest into tech on that side, like MIDI,

keyboards, drum machines, whatever, different than the one when AI came along? That's

a good question. So I basically am the product of a home where my grandfather,

my English, my British grandfather was in the British army during the World War II

and he was in the Royal Corps of Signals and the Royal Corps of Signals was the

radio operators, basically the guys who were fixing these and making these valve

based radios for the troops to use and he was always fascinated by electronics and

engineering. Anyway, by the time I met him he was quite an old guy but he had

this shed at the bottom of a garden And in the garden shed were all these manner

of circuits and capacitors and fuses and electronic, you know,

machinery. And he sort of got me very interested as grandfathers do in the thing he

loved and that was, you know, making electronics. So I had a very early introduction

to gadgets and electronics and that as a musician, I I was learning piano in the

early 80s and then I started getting very interested in electronic music. I mean

Jean -Michel Jarre was doing things like Oxygen and you know, even people like Abba.

I remember Abba's last album. The visitors had these amazing Yamaha synths on it.

And so I started listening to synthesized music because it was more interesting than

Bach and Mozart and all the other, you know, my churny excess. And so I started

getting really interested in synths and From that point on, yeah, I got the bug,

and in the late '80s, there was a great music shop in Manchester called A1 Music,

and they had loads of really amazing stuff I could never afford, but they used to

lately go in and play with it to sort of torture yourself. You couldn't afford it,

but you could play with it.

It's haptic, you know, you can push on it, you can use it, you can put it in

your hand. And that's maybe what's different with AI. I mean, yes, you can be on

the computer and click on it, but you cannot touch it. I mean, and it's interesting

how that's gone full circle, because I remember, for instance, this keyboard I had

the Bit99, that was all addressable via a single LED on the panel.

And there was no knobs and dials, really, there was two faders. And it was the

doped to all of the analog synths that had been around and everybody thought, you

know, direct digital control of synthesizers like the Yamaha DX7 and things like that

was the way to go. But ironically, everything goes full circle and now everybody

loves knobs, buttons and, you know, Euro -rack and all this. It's hilarious in a way

because when you run old enough you see the whole circle complete as now everybody's

back in the world of the numbs and dials. But yeah, so I got into computer music

quite early and I was listening to a lot of electronic music. Then the obvious

candidates like DeFesh Mode, people using the sort of emu emulator and then a very

interesting German band called Propaganda. Propaganda wrote this amazing record called

A Secret Wish which was produced by Trevor Horn and it was really one of the first

albums I ever heard with Fairlight, CMI on it, that was really amazing and this

electronic reverbs and things. And that album really changed my perception of

electronic music. There was a lot of amazing samples and drum programming on it.

Yeah, it's interesting you all mentioned this. I mean, I will have a talk soon here

in Montreal about AI and music in general. And I have this thesis that I say AI,

I mean generative AI is these days also a little bit punk in the sense that AI

enables because the punks I mean there's a lot behind the idea it's not just like

making music but I will come to that later but it is punk in the sense that

everybody now can make music music like they want to I mean the punks were not

able to play music they were just putting three accords and they were not able to

sing but they were getting somewhere with the music where they would have never been

without the music and in that sense I have the feeling AI in this is possible to

create some punk songs like not real punk songs but the the attitude of punk that

everybody can make music these days and that was like in the well it was the end

of the 70s beginning of the 80s when that oh 80s was punks already a little bit

dying I have to say, but yeah, would you agree with this? - Yeah,

for sure, well, yeah. - I mean, Throbbing Grissel, with the obvious example of that.

I mean, Throbbing Grissel, Chris Carter, used to build synthesizers for that band,

you know, and they were like recording in the '70s, late '70s. And then obviously

also very interestingly, Joy Division from Manchester, I always thought it was very

interesting 'cause Rob Gretton from Factory Records a few years ago. He published his

memoirs and it was really interesting to look at the tour receipts for that band

because Joy Division and New Order spent a considerable amount of their money on

synths on the road. More than guitars or drums, they were buying the latest and

greatest synthesizers they could get their hands on. And so there was a kind of

crossover where punk started playing since for sure, you know, and, and, and I

agree. I think the, the essence of, of punk and this idea of every man and every

woman, everybody being, having a democratic access to these art forms that were quite

rarefied and demanded, you know, in the old days, demanded money and years of your

dedication, and we're sort of closed to everyone. It definitely is an energy that

sits inside of electronic music, and I think that's what sampling did as well.

Because if you look at, for instance, massive attacks, they were using the Akai MPC

to start off their recordings after being DJs, so they started off as DJs and the

Wild Bunch, and then they started getting into sampling and using Akai and MPC, sort

of, and rack -mounted samplers. And a lot was the energy of, you know, cutting and

pasting collage, really, music and collage, where you could, if you couldn't, you

know, you couldn't score for a string orchestra, where you could sample a string

orchestra and try and use the strings, you know. And I think that's true. With AI,

it's similar. I do think, I think some people won't appreciate the analogy,

but it is similar in the sense that it democratises music, you know. I gave a talk

a couple of months ago and I was doing a thing in Novi Sad in Serbia and I had

to talk about my experience of music and AI. And I just recall, there was

definitely a move in the 80s where famously,

I think the BBC Orchestra, there was a BBC House, in -house orchestra, and they used

to play on all the TV shows and the theme music for TV shows. And the, I shows.

And I think it was the Fairlight came out and they started going on strike and

basically orchestra went on strike with the Musicians' Union because they were

complaining that these samplers were stopping them from being used as orchestral

musicians and therefore they would go on strike. And I think the BBC one week, or

a couple of weeks, went dark for Top of the Pops because there was a strike by

the Musicians' Union to protest to these new angle samplers. So I think that in

some ways... There is an allergy. Yeah and I think the culture is the same. People

are now feeling threatened by the fact that music is generative and synthesized.

Do they have to be? I'm not convinced. I don't think it's a threat in the way

that people think it is. I think there's a lot of things to unravel with AI.

And I think there's an anti -technology narrative, which is an anti -capitalist

narrative that's quite difficult to unpick. And people are just bashing anything that

is technology because they feel it's art of the whole system that's bringing about

climate change. And these things are very, suddenly there's a lot of complexity in

these technology arguments that is not clear from a perspective of the old -fashioned

idea. because in the old idea, technology was innovation and moving society forward

and seen as a force of good. There is a form, I think, of a backlash now where I

think the excesses of Silicon Valley and some of the demonstrable money laundering

that's gone on with tech, that's left people disillusioned and feeling like it's part

of the problem, not the solution. But I feel like from a, I mean, that's not a

whole other conversation, but I think my perspective is I don't I don't see AI

music as as any more of a threat than really using, I don't know, samples and

using sequences and using arpeggiators. I mean, you could argue that everybody could

have lost their mind about arpeggiators, and they could have lost minds about auto

programmed, you know, Even the Yamaha home organ, where you'd press the key and

you'd get the chord accompaniment. You could say that was a really form of putting

musicians out on their jobs, but you know, it's... Yeah, you described it pretty

good. I mean, that's the thing, the argument I'm always bringing, and I think I

said it already here in the podcast, is like, if you listen to music these days

and you love a song and you say, "Okay, this is my song, I love it,

I embrace it, I cry to it. It creates emotions for me I've never felt before. And

then somebody tells you that singer, because that's what musicians told me all the

time. Whenever there's a song out there, you do whatever you want with the song.

It's your song, and you put your emotions, your feelings, your ideas on it. When

you take that song, it's yours. And if I tell you then in the end, this song was

written not about a lover, it was written about a cat, and you made out of the

song your song because you thought it was a song about a lover and it's your song

it's your song and that's the same with AI if you listen to a song and you have

emotions with that song in the end and it's your song why should you not listen to

a song that is made by an AI then if it's your song if music creates that with

you it's your song so technically not a lot has changed for me in that sense but

And that's what you also mentioned. The problem is these days, and I do see this.

I think it will be, it's amazing for creating art. It will open doors we have

never seen before. But I always have a problem with the democratizing word of this,

because yes, it is bringing the money to big tech companies because they can easily

create platforms where all the people put their So money in there to pay for

somebody who has been used, who has used artworks from other people.

That's my opinion. And I think it's a big political problem we have to solve. And

it's not the problem that we have these things. It's a political problem we should

solve because democratizing me is, yes, I pay less for an orchestra, but on the

other hand, five million people pay less and they pay to one company and that's the

problem and my yeah I mean so you know there's always these very big shifts

societally so my grandmother was born in 1918 in England and she was born at the

end of the First World War and she used to talk to because I worked in music tech

and I like music and so my grandmother who obviously loved to the fact that I

played music and she was a proud programmer there. She remembered, and I remember

her telling me this when I talked to her about the internet in the '90s. So I was

really early on the internet and I was working with David Bowie at EMI in the late

'90s and Bowie Net. And I tried to explain this, and I tried to explain my job to

my grandmother, which is always an interesting idea.

- I know that feeling. - But she came up with this really amazing analogy and she

said, "Oh, I remember in 1927, "when I was only,

I think she was like nine years old,

"I remember going to the cinema "and everybody went to the cinema in those days,

"it was cheap and it was entertaining." And she said, "I remember going to the

cinema "and it was silent. "And then one day in 1927, "a guy called Al Jolson

recorded the first talking motion picture. It was called "The Jazz Singer." And it

came out and it was the first movie with a soundtrack that anybody ever saw. And

she said the transition from silent films to talkies meant that all of a sudden

live orchestras and all the people who are employed in live orchestras had problems

keeping their jobs. Because up until "The Jazz Singer," unless you were very wealthy

and you could have ordered a record player, which was the sort of upperclass, middle

-class thing to have. You had to go to the local bar or the local vaudeville or to

the park to listen to the brass band and you had to go and listen to live music.

As soon as the films came in with soundtracks, a bunch of musicians found themselves

unemployed, right?

And even live films, live accompaniment used to happen in silent films. You know,

the music's played longer, this silent movie. But so it changed and suddenly

everybody was out of work and it was the displacement of the live orchestra. Tens

of thousands of musicians I think lost their livelihoods in just a few years doing

that. And you know the gig of scoring every show and every evening sort of as they

would did, jobbing musicians sort of disappeared. And you know The industry,

though, adapted and musicians started going into film studio orchestras because music

still needed orchestras, right? And Hollywood and radio networks as well, radio

networks, radio bands, orchestras, people went into the radio studios to start playing

music through the radio. And then there was also retraining. And I did a bit of

study into this because I thought, you know, I'm into history. My mother was a

history teacher and history is a good way of understanding, you know, things aren't

exactly the same age generation or every 100 years, but they do have echoes. Because

humans, you know, we wear different clothes and drive different vehicles, but we

still have the same emotions and the same drivers. And so, I think it's the

mentalists in those days, they retrain some of them went into different jobs,

obviously. And what was more interesting that was around then that I haven't seen

anything of in this era is the unions. So the music union in the 1920s and 30s

helped unemployed musicians because they had a union and union rates and everybody

paid a subscription to the union and when everybody fell on their ass union was

there to pick them up and also retrain them and you know and then people sort of

moved into sound engineering and soundtrack there's an orchestration in the 20s and

30s, one of the things I think is really interesting in our culture is that while

all of this theory has been going on about, first of all, it was streaming and

record industry falling on its house and piracy, and now it's AI and it's stealing

people's music and scraping people's music, where is the Where is it and and and

where is the performing rights society and whereas a gamer and ask up and all those

people Well a gamer a gamer is a gamer is suing soon. All right. They are but

they but the seal feels to me quite late Right, so let's let's play some role

-playing You are in one of these rights organizations or a union and you are paid

by the members of that union to look at the day -to -day administration of their

rights and of their issues around their employment instead of that. Why did these

things that were on my radar and probably your radar, why were these things not on

those people's radars five or six years ago when deals are being done and when

things were going on? I think they were just not able to cope with the speed.

I think they were just, they were not understanding it. And one thing I think one

important thing you have to understand with all these rights with these companies is

they sometimes still think in old patterns.

And those patterns of old copyrights don't work anymore. I think this is the biggest

problem. I think they have to adapt to a modern life in which the copyright system

is a little bit outdated. All of it, very outdated. I think The trouble is, the

shift is how you say, quick. But, you know,

I do think, I'm not blaming anyone here, but I do think it's interesting to think,

and it was the same for me when lockdowns happened and COVID happened in the UK,

especially. There was a huge problem with unemployment where freelance technology and

technicians, producers, Live engineers, live, you know, roadies,

everybody involved with live entertainment. There was suddenly no money and in the UK

You did not get any relief from the state Unless you had a limited company and if

you had a limited company you were able to claim this thing called furlough Which

was going to give you maybe sixty to eighty percent of your income based on a

government allowance The trouble is with all these people working in the music and

production industry was they didn't have limited companies or freelance self -employed

people. And so again, there was this problem where you realize that, you know, I'm

not just some raging Marxist, but you do realize that the musicians union and a

union for musicians and a union for songwriters like, you know, the various

songwriters guilds, obviously, but those kind of things, like BASK, I mean, I'm a

member of BASK, you know, but these you know, but these really quaint organizations

that don't seem to have a bit able to keep up at all with any of the issues that

are going on. So maybe there's a new way of doing stuff where, you know,

collectively people can have some control. I think the trouble is without being to

do me about it, I think the cat has already run out of the banach.

I don't think you can't put the lid back on these music models. So like,

interestingly, when I was talking to Douglas Eck at Magenta, I did ask him,

I said, "Hmm, so, you know, obviously you've got all of YouTube, are you going

around, are you going around scraping all the YouTube music?" And he didn't answer

my question. And so what we have to assume is that really these, especially Google

and please put but like this. We're obviously building these models for, it's

probably 2016 -17 and these models have started to be built. To be able to go back

into those models and reverse engineer and try and find where your song is in all

that corpus of, it's impossible. So the only thing, and this is an argument that I

haven't been around for a while, but I remember this was always a good one.

Because I I'm a man of a certain English. I remember when file sharing was the

issue. Napster turned up in the late '90s. Suddenly everybody was sharing music on

Napster. And then Torrance turned up in Lime Wire and things like that. I never was

going, oh my God, oh my God. How do we make money out of this? We can't, we

can't, we can't. I still maintain the logical answer to that problem then is the

same as the answer to the problem now. Who are the beneficiaries of data streaming

products, such as mobile phone networks, internet service providers? Who are the

beneficiaries of those companies? Well, in the UK, it's British Telecom, and in

Polymerarm, it's like Orange Telecom, and you've got T -Mobile, all these people. Why

if you're a bar or a hotel or you're another public venue and you play live music

or recorded music, you have to pay a license for that. Why is there not an

equivalent for all of these people offering streaming data services? Take it for

granted that the majority of your users at some point are streaming music that's

probably not paid for or even or even is paid for maybe to Apple Music or Spotify,

whatever. But why don't you just ask them to put a percentage or a couple of

percentage of their profits every year into the public performing right society

basket? And that was a very unpopular suggestion of mine when I was at EMI.

And I think it would still be a very unpopular suggestion now, but to me, it's

logical.

I totally agree. I think that model of giving out licenses is one idea to get the

money back to the people who deserve it, but in many situations,

not only the companies you've talked about, but also if the companies who generate

AI music should pay for this in a yearly license fee or whatever.

It also would be a little thing to put on top of the little amount of money,

which is existing for the artist, anyhow. But this thing is the thing that cannot

be done by just saying, "Okay, we're going to do this. We're going to sue them."

This is a political thing, and that's the problem. It is a thing of, yes, what the

unions should do. It's a political thing. It's a decision of the And that's the

problem where we're heading right now. In the politics, there are more tech bros who

decide what the politics have to be. And that's why it's so hard, I think, in my

opinion, to get the money from those companies who profit from it. - Yeah, I mean,

I agree. And so, you know, I was actually part of the problem. And funny, my

girlfriend, my girlfriend goes, "Oh my God, you were part of the problem." Because I

remember in 2001, I was working with David Bowie and we were thinking about mobile

phones and I'd worked for a wireless access protocol forum with a WAP forum and so

WAP was the first version of internet on phones. I mean, this is how old I am,

GPRS, Nokia phone, was the first ever mobile internet phone.

Well, I'm old now too, if you tell this. But I was always interested in phones and

then obviously phones started doing ringtones. They were terrible and there were like

these beeping sounds. Anyway, at one point I got wind of Nokia bringing out this

new phone called the 7650 and it was going to be this new flagship phone with a

colour screen, a one megapixel camera on the back and it was going to play

polyphonic midi ring turns. And I was like, oh polyphonic midi ring turns, I mean I

knew what those were and they would sound a lot better than the BP beep, you know,

phones of previous years. So we made a beeline for Nokia and while I was at EMI I

actually got in touch with Nokia in the UK and we did a deal and David was the

first artist to sign his publishing rights over for mobile phone ringtones on this

Nokia phone and so the Nokia phone came preloaded at retail with a bunch of David

Bowie ringtones on it and David loved showing off, he loved doing things for the

first time and you know being the clever one, he of it first. And so he loved

that. But what I realized we did at that point is we opened the door to another

company that you will have heard of called Apple. And Apple had just brought out

their first version of the iPod. And I remember David's manager looking at what we

did with Nokia. And he was also working with, he wasn't managing, he was working

with U2 at the time. And lo and behold, our preloaded Nokia phone with ringtones

turned into the U2 iPod.

a tricky road, because like you said about the tech bros, unfortunately,

there was a generation of young people who remembered being charged a lot of money

for CDs. And when you only wanted one song, you had to pay 20 euros for the whole

CD. And a lot of people who hated that then worked in tech and decided the music

industry was gonna get it, you know? And I think that's-- Although I can say,

I still like albums. Yeah, I love albums, I love albums. I mean, you discover songs

which you would have never listened before. That's a magic of an album also. Yeah,

at the end of the day, that was where the tech business started understanding the

music and then eventually film and all those things were going to make their devices

much more attractive, you know, because obviously the killer blow was when Jobs

decided to build a phone that was an iPod with a phone in it, and that was the

end of everything, you know, the beginning of everything. So it's interesting. I

mean, at the end of the day we're sort of, you know, going around the history a

lot. I suppose the point I'm making is that the relationship between technology and

music has been around for as long as electronic engineering is happening. I mean,

you know, if you wanted to be anal, you could say that Engineering and music has

lived together since anybody wound a string tightly on a wooden device and plucked

it because that was the technology, right? Making music and then printing, printing

press, you know, yeah, you know, the Kraftwerk song, pop, what is it called, pop

music, maybe? No, there's a Kraftwerk song where they sing in German, music will

always continue as a container for new ideas. And that's what it is.

Music has always been in the forefront. If it comes to new ideas, they've always

tried it out in the beginning. So yeah. And this time, with AI also,

music was pushing it a lot and the discussion about AI started a lot also with AI

with AI music, because somebody was listening to a song from Eminem,

which was not spoken by Eminem, but was created by some kid in New Jersey,

I don't know. And that's how it started, and that's how the big discussion about

this kind of got into the mainstream. That's what my feeling is, and yeah, it will

continue this. But in the end, I mean, to sum it all up a little bit, like what,

I mean, you say there's a unions, I mean, obviously there is something happening

which is not going in a good direction with the music and the AI, And I know we

have to change and artists will suffer, I'm pretty sure. But on the other side, I

always think human music will always be the precious thing we will keep. It will

not disappear. But what can we do and where will we go? So I think the answer I

was almost heading towards with this story about Al Jolson and the jazz singer in

1928. I think my understanding as a musician and performer,

as somebody who's played music and bands and on stage and in front of audiences.

And also a musician who's recorded in studios and recorded and done that too.

My inclination to be an optimist is to suggest that what we should be aiming for

is not necessarily for politicians to try and ban AI and,

you know, Paul McCartney just wanna ban or at least get legislation to protect

musicians and this sort of stuff. I think that's insightful and needs to be done,

but I think what's really interesting, I was recently in the Czech Republic and in

the Czech Republic, all the school kids get free music lessons, still. And

culturally, That is a very interesting thing, because in the UK you don't get music

lessons of free anymore. My son is 14 and I have to pay for his piano lessons,

you know, and the era... They get it in the school, like you go to school or

outside of school? In school you get free... I mean, when I was at school, you

used to get free lessons with an instrument for a few years. Steve, you liked it.

And my inclinement would be to suggest This, the answer to the problems lies in

education and allowing young people the opportunity to try their hand at music and

various other things. We ended up with this de -skilling of the music business

because of the political inclinations to reduce funding for the arts.

So, you know, in the 90s and the 90s everybody had to learn the code, coding,

coding, coding. You're only worthy member of society if you know how to program

computers and if you're an artist well good luck to you you know and I feel that

that's missing some of the point of the self -humanist tradition and the Renaissance

tradition and the enlightenment which is that if you were to give children especially

you know I mean one of my favorite bug bears is this thing with VR and AR so if

you add the numbers between Google meta, Apple, Microsoft, they've blown like 140

billion billion dollars allegedly on building these AR /VR headsets to no great degree

of social impact. I look at that number and go, what difference would you have if

that number amount of money was spent on schooling children and giving them lessons

on musical instruments and notation and music appreciation and just gave people a

rounded education so that they could decide or we could discover whether they had a

talent for making music. The joy of music is making it together. You can do it on

your own and you can do it with a screen in front of you with some clever AI

doing question answer and playing along with your chords and suggesting rhythms and

cascading arpeggios. You can do that, but that is not the same energy,

the same spirit of the energy of sitting in a room with people making, even if

it's basic beats and bashing things or, you know, playing basic instruments, nothing

has replaced that in my mind. And I feel that without being a purist and too much

of an idealist, I think the answer with the whole AI thing is that hopefully what

we could do is become more human and try and re -establish these kind of smaller

gigs that aren't like massive

stadiums and you know this try and go back to some of the grassroots of some of

the smaller time venues locally and I would but if I if I run the world I would

definitely be in the business of trying to promote there are more local grassroots

music making give local venues a bit more time money and get more opportunities to

get people in there and socializing. Now, the trouble is there seems to be a

political sentiment in the modern era now that artists have to be just,

we have to be suspicious of artists. You know, they're artists are non -conformists.

They're spreading interesting ideas that you might not want people to think about.

You know, I think it was very interesting in the current era, having listened to

the protest music of the 60s, for instance, and Dylan and the Dawes and the

Beatles, there's literally no one I can hear in the charts writing songs about

what's going on in the Middle East, what's going on in the climate, what's going

on. There seems to be a lack of, and whether this is because the gatekeepers are

very cautious, like the Apple Music playlist people and the Spotify playlist people

and the radio, There seems to be very little breakout of what I would argue is the

old, punky, hippy energy of criticising the society you're in and...

Although they do this, although they're, I mean, maybe they don't do this in songs,

but they do this quite often in social media. Yeah, they do. I have to say, I see

a lot of musicians who raise their hands and a lot of issues and they do this on

social media these days. That's what I have to say as a defense for those

musicians, although they're not these songs. And one thing I want to just give you

maybe one last quote to do think of, because you just said this, people like to do

their music with each other in the room and they make music with each other. And

then there comes this quote. You heard this quote of Mikey Shulman from Sudo, did

you hear about this? And he said, "It's not really enjoyable to make music." No, I

quoted it the last time here on the podcast, it takes a lot of time, it takes a

lot of practice, you need to get really good at an instrument or really good at a

piece of production software. I think the majority of people don't enjoy the majority

of the time they spend making music. That's what he said. - Yeah, well, I do

remember that hearing that quote. - And I think what I said about it, it was like,

of course he has to say it, he wants to sell his product. And if he says it's so

much fun to make music, you wouldn't sell his product. That's why he has to say

it. - Yeah, for sure. - That was my explanation. - Yeah, for sure. And I think

that's, you know, it's interesting that if you look at the history of recorded

music, can you look at the Berliner disc, right? And you look at the original

Edison wax cylinders. When the wax cylinder first came out, it was a dictation

machine. It was designed only for recording voice and then somebody came up with the

amazing idea that it could be useful music and the music publishing and recording

industrial complex if you like that you know I worked for EMI Records in the 90s

and that was the British version of that, it was 1897 you know and it was a

company that did everything from make x -ray machines to printing presses for millions

of records to having record companies you know like polyphone and the Beatles.

Somebody came across the idea of creating music publishing to be able to sell more

of these disc machines, right? So the music with an afterthought for the fact that

you wanted to sell the hardware. And you could argue in some ways even Steve Jobs

did that. He was obviously a fan of music, but he realized that music was going to

sell more iPhones and more iPods than anything else. More than spreadsheets, more

than web browsers, more than ringtones. It was the fact that these phones were going

to be your Walkman. So I think getting back to the point of AI,

I would argue that we are definitely in the world of computer -generated music.

That is happening and it's going to get better and better and I think it's going

to get harder and harder to distinguish between human performances and writing and

machine performances and writing. I think that's a given. I think what the antidote

for musicians is, I think, like this idea of after the talkies in the 1920s in

Jolson, people Going into different fields like going to studio orchestras going into

engineering and stuff around music You know, I have to tell you I was not

successful as a musician when I was young I wanted to be in a band to be famous

and I wanted to go around the world and we know what can be cool I didn't manage

that But what I was good at was I was good in the studio and I was good with

computers and Cubase and tech and I was good with synths and samplers and I ended

up moving sideways and working as a producer and working as an engineer and then

the internet turned up and I moved sideways again and this time what was interesting

I converged my interest in engineering with music and I worked on the internet and

the web and what I would argue is that if you love music and you're passionate

about it then there is you can lead a musical life you don't have to just sit

there and be the the only few in the morning is play the guitar and you need to

make a living from it or you'll never do anything else. You can live a musical.

Some of the best advice I was ever given was an old friend of mine called John

Grant and he was a drummer in a golf band in the 80s called Ghost Dance and I

remember being really frustrated at one of my 20s. I wasn't making it, I wasn't

making any money and I wasn't going to be famous, I wasn't going to sign and he

just looked to me and he said "Andy, just lead a musical life"

And I just, I think that, I know that's, I don't want to sound glib. And, you

know, if you're watching your revenue from the thing you did as a thing that you

got paid for, disappearing, well, I feel bad about that. But everybody has the

ability to evolve. A music evolves the way we make it, the way we listen to it

evolves. And the art form itself evolves. And I feel like humans evolve, so I think

to hold on to a vision of the past and a model of the past and go, "Oh my God,

it can only be this." I don't think that gets us further along the line, you know.

I think this is the perfect ending.

You just said the best phrase to encourage people in the end. Thank you very much.

It's That was

the new episode of the Iliac Suite, thanks Andrew Melchior again for your time and

amazing stories, it was a pleasure. If you have any questions, mail me at mail

@theiliacsuite .com, mail

Point .com, that is the address where you can reach me and you can give me any

feedback or also any suggestions who you would like to invite for one of the next

episodes here in the Iliac Suite. Thanks for listening humans, take care and behave.

(upbeat

music)

Creators and Guests